Is it Done Yet?

By Diane Fechenbach

Remember road trips as a child (or parent of a child)? Remember asking “Are We There Yet?”, then thinking this is the loooongest trip ever, it will never be over, oh, look, there it is! – aack! that’s not it, what do you mean, another HOUR?

Art is no different. The most common question asked by artists – whether new or experienced – is: how do I know when it is done? When is the painting finished?

There is an old saying: It takes two people to paint the painting: one to hold the brush, and the other to tell them when to put it down and step away. While I have never experienced the Art Fairy sweeping in and snatching the pastel out of my hand before I could ruin the painting, I have found a tip that serves me well. Read on.

Start at the beginning

The best way to tell when you are done with the painting is to know from the planning stage where you are going to end up. Ask yourself what is the reason you are going to create this painting? I call this the WHY. As in, why are you taking the time, energy, and art supplies to make this painting? Or, why did you pick this subject? The WHY can be “I love the light on that flower/tree/face”, or “the color red is so much fun to explore.” The WHY is a specific thing. For example, the texture of that one flower, not all the flowers and every single leaf.

The WHY is what prompts you to start the work. Sometimes it is called an “intention”, or the “story” you are trying to tell. The key to this is that each painting has ONLY ONE WHY. Rather like going to the airport: you get on one plane to one destination at a time. Today I am boarding a plane to Seattle. While I may be thinking about Boise, or Memphis, or Boston, those are not part of this plane ride. THIS trip is to Seattle. So it is with your painting: one gig today. Something else next week.

It is actually pretty easy to identify the Why for your project. Ask yourself what was it that made you stop in your tracks to set up the easel or take a photo? Why choose those flowers for the still life? What took your breath away? Use that as the WHY for the painting. This Why is the star of the show. The Diva. The lead guitar. The soloist. Everything else is there to make the star shine. Everything else becomes supporting cast: the backup singers, the costume department, the roadies loading the trucks, the distant trees, the flower pot. All helping us love the star player. Note that if the supporting elements start attracting too much attention, they compete with the star and need to be toned down. Focus on the Why.

When you have accomplished your WHY, you stop painting.

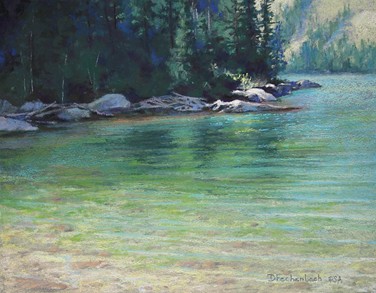

In the painting, “Ankle Deep”, at the top of this blog, my why is the water lapping at the rocky shore. It was what made me stop and take the photo.

Notice how much of the painting is water. The ripples and rocks in the water have more color and texture than anything else. I was really interested in the water. The trees, not so much. The background trees and rocks describe the edge of the lake but have little detail. They were not eliminated, merely played down so as not to compete with my Why. The distant hills are pushed to the back with atmospheric perspective and a few smudgy marks. The focal point is the sunlit rocks at the “rule of thirds”, but the focal point does not have to be the why. The why is my motivation, the focal point is the viewer’s payoff. Sometimes they are the same, sometimes not.

Stronger paintings have one thing to say.

This next example is two paintings of the same scene painted at different times. In “New Year Blues”, above, I loved the reflections and texture of the frozen water. This is my Why. Background trees are played down with general marks, little detail and subdued colors. A neutral wall. The painting does not work without them, but if they were presented in bright colors and carefully drawn, they would compete with the water. I wanted them to sit in the background to establish the setting. It was hard to resist the urge to make the trees colorful and more interesting. If I had done so, there would have been two strong statements competing for attention. The almost square format allows plenty of room in the foreground to extend reflections and describe the edge of the snow at the water line. Since this painting was about the water, I declared it finished. Those trees could be another work. As in the next painting.

“Platte River Blues”, below, is about the bare winter trees and the snowy riverbank. Notice this painting is not about the river. Your eye goes immediately to the color and texture at the back of the painting. Snow patches are larger and have more interesting color notes. Bushes are a little bigger and brighter. The river reflections are more subtle and bushes in the left foreground less vibrant so they act as supporting cast. The horizontal layout emphasizes the stretch and pattern of hillside and the rhythm of tree trunks from left to right.

A plein air example:

“Monarch Morning”, below, left, is all about the backlit bushes. The vertical composition directs the eye to my Why. This scene is at the edge of a pretty lake with paintable views everywhere. Early in the morning I loved the light coming from the left behind these trees. The foreground trees have minimal definition on the shadow side because the emphasis (my why) is on the glowing grasses and bushes. Background trees are loosely blocked in. Had I put more detail in these trees, they would have caught the viewer’s attention and

drawn the eye away from the star of the show. They are less important and become supporting cast. The painting is finished without them. The second photo on the right shows the scene behind me after the sun moved.

“Monarch Blues”, below, is painted from the same spot. The sunlight is no longer my why. Now I am interested in the color of distant haze under slightly overcast skies. It is my new why. All my planning has gone into describing that distance. The palette has cooled off, warm sunlight is downplayed, repeating shapes of distant mountains is emphasized. The trees and bushes on the left become supporting cast. They are necessary to move the viewer’s eye to the back of the painting. But the longer I stood there, the more I wanted to work on the foreground trees and bushes. (After all, I had just painted them in the last painting.) This painting is not about them, so the painting was finished and I walked away.

Finding another painting

Occasionally, I feel like there is more to say about the same subject.

“February Shadows”, below, was from a photo taken out the car window. I loved the shape and colors of the shadow: my Why. The shadow is the star of the show. A large stand of trees and bushes in the background are downplayed to keep the emphasis on that shadow shape receding into the distance. A foreground tree was eliminated and grasses and bushes were used to direct the eye back and forth from front to back echoing the shape of the shadow. When the snow shadow was described with colors and textures, it was time to stop.

I dislike painting the same piece again and again (original art should be original, not just a rerun). However, reversing the subject matter provides a new look at the same source material. New material has a new Why as well.

I was sorry to lose the trees in the background of the reference photo for “February Shadows”, so a few years later I painted “Saplings in the Snow”, below. The trees and bushes are now the star of the show with prime placement and saturated colors, and the snow shadow is supporting cast. Notice the shadow is not full of vibrant colors or texture and its interesting pattern shape is softened. The painting was finished when the trees and bushes were completed even though the foreground shadow shape is still in a block in stage.

In both these paintings, the temptation to keep painting all the beautiful textures and colors of snow, bushes, trees, was great. The result would have been loads of lovely detail but a weaker message in the painting. Besides, once you start detailing and tweaking every inch of the painting, when do you stop?

Ah, we are back to the original question. How do I know when my painting is finished?

Your goal in creating the painting is to celebrate the primary thing you loved. The thing that made your heart skip a beat and nailed your feet to the ground. Tell the viewer about that one exciting thing. The other things you liked can star in different paintings on another day.

Remember, even cameras focus on one thing at a time regardless of how much is in the view finder.

Stop painting when you have described your Why …. And at least 30 minutes before you think you should have stopped.